(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Copper, aluminium, zinc and tin all hit record price highs in March. Lead was the only LME base metal to miss out on the super-bull party.

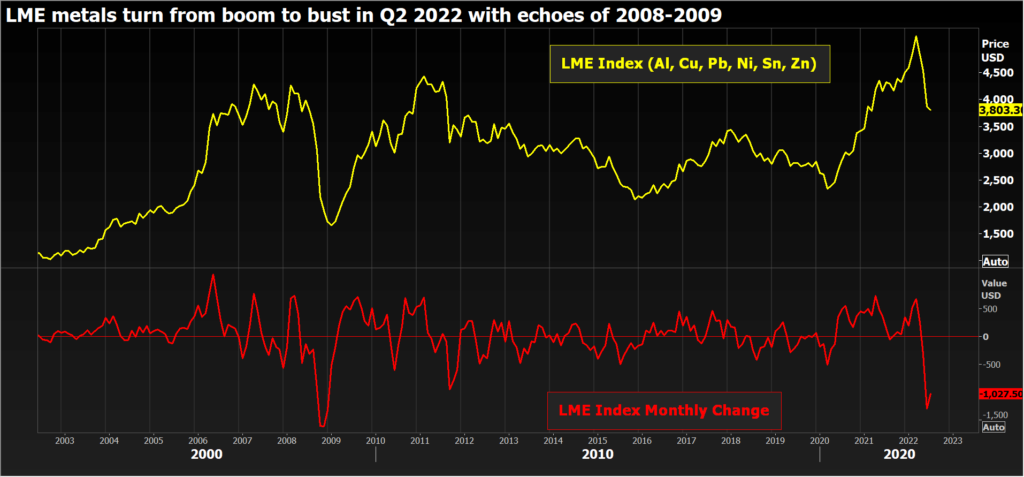

After the March melt-up, however, industrial metals are now in meltdown. The LME Index has just experienced its sharpest quarterly fall since the global financial crisis.

The pivot in sentiment from super-bullish to super-bearish has been the Feb. 24 launch of what Russia calls its “special operation” in Ukraine.

Fears of sanctions against Russian metal helped drive prices to those record highs in March. But flows of Russian aluminium, copper and nickel have so far been largely unaffected.

Rather, traders are now focused on the recessionary impact of high energy prices as the Russian invasion grinds on.

Bears come out to play

Investor positioning across the industrial metals has flipped from long to short over the last few weeks, with systematic funds responding to chart breakdowns and downside price momentum by increasing bear bets.

Money managers were net long of the CME copper contract to the tune of 42,000 contracts at the start of April. The net short now stands at 25,402 contracts, the most bearish positioning since April 2020.

The last few remaining bulls are throwing in the towel. Funds’ outright long positions have shrunk to a two-year low of 33,926 contracts.

This is symptomatic of the broader investor landscape in metals, with heavier-weight funds trimming passive long exposure and systematic trend-following funds selling into price weakness.

LME broker Marex estimates there are now significant speculative short positions across the whole complex in the London market, several of them close to multi-year highs in terms of size.

China to the rescue?

It’s not hard to understand investors’ bear rationale.

High energy prices are fuelling inflation and central banks are responding by tightening policy.

They are also starting to chill manufacturing activity.

The latest string of purchasing managers indices captured stalled growth in Asia, the United States and Europe.

China is the potential bright spot in the global economy, with manufacturing activity expanding in June for the first time since February as the country gradually emerges from rolling lockdowns over the first half of the year.

However, there’s plenty of caution that China’s recovery may yet be held back by Beijing’s zero covid-19 policy, with several cities tightening curbs over the weekend as new cases emerged.

Tellingly, Chinese players are themselves playing metals such as copper from the short side.

Marex estimates the collective short positioning on the Shanghai Futures Exchange’s copper contact, expressed as a percentage of open interest, is as high as it’s been since 2008.

That speaks to a lack of conviction about the strength of any recovery in the world’s largest metals user.

Liquidity trap

The speed of the base metals price collapse is partly explained by a drainage of liquidity on the London Metal Exchange in the wake of its controversial suspension of the nickel market and subsequent cancellation of trades.

LME volumes have been sliding ever since. Trading activity in the second quarter was down by 13% on the year-earlier period and by 21% on the first three months of 2022.

Nickel is the most obvious casualty, prone to sharp price swings on low volumes, but this is a broader issue for both the LME and the physical supply chain.

Lower investor and industry participation on the LME leaves market action increasingly dominated by short-term systematic funds.

The resulting elevated volatility is reducing financing capacity for physical players as banks reassess their exposure to the metals sector.

Revenge of the micro?

It’s possible such financing constraints could lead to inflows of metal at LME warehouses, reversing a defining trend of recent months.

Total registered stocks of all metals amounted to 696,000 tonnes at the end of June, down from 2.36 million tonnes a year earlier.

Available LME zinc inventory is currently just 22,050 tonnes, which is why time-spreads have been tightening, the cash premium over three-month metal spiking out to over $200 per tonne last month even as the outright price was falling.

Such is the disconnect between micro and macro right now. Recessionary gloom is crushing all micro positives such as zinc’s dangerously low inventory cover.

Or the lengthening list of aluminium smelter curtailments in Europe and the United States, as high energy prices take a toll on a notoriously power-intensive sector.

Alcoa has become the latest producer to announce a cutback of 54,000 tonnes of capacity at its Warrick smelter in Indiana, citing “operational challenges”.

The whole Western aluminium supply chain is operationally challenged right now. So is that for zinc. Physical premiums for both metals remain extremely high, particularly in Europe, where regional production losses have been compounded by logistics problems.

It’s a sign of the extraordinary supply tensions in the West that China has been exporting both aluminium and zinc despite high tariffs on outbound shipments of refined metal.

With no relief in sight for European power prices, regional metal smelters are facing margin pain until further notice.

The LME paper market is pricing in a recessionary hit to demand while simultaneously ignoring the still bullish fundamental story of low inventory and continuing supply-chain stress.

The mismatch is increasingly stark, and it may be only a matter of time before ever larger short positions clash with ever smaller stocks.

Combined with patchy liquidity, there’s a good chance there’s more metallic boom and bust to come in the second half of 2022.

(Editing by Jan Harvey)

No comments:

Post a Comment