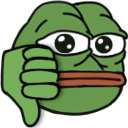

SQM’s evaporation pools in Chile’s Atacama Desert. (

Image courtesy of SQM.)

https://www.mining.com/web/lithium-king-crowned-in-dictatorship-sees-3-5bn-fortune-at-risk/

Few people are better positioned for the electric-vehicle revolution than the billionaire Julio Ponce Lerou.

He retired years ago, but the former son-in-law of late dictator

Augusto Pinochet is still known in Chile as the lithium king. And Ponce

has never been richer: The shareholder group he leads has seen its

approximately 25% stake in SQM, the world’s No. 2 lithium miner,

quintuple over the past seven years amid record profit, increasing the

value of the portion he owns to $3.5 billion.

Sign Up for the Latin America Digest

Like billionaires across the globe who have seen their wealth soar,

from Elon Musk to Chinese property moguls, Ponce, 76, has become a

target at home amid the boom times for lithium, a key mineral for making

electric vehicle batteries. One of his main adversaries may turn out to

be Chile’s 36-year-old president, Gabriel Boric, who supports a

constitutional rewrite that may impose environmental curbs on mining and

wants to create a national lithium company that could compete with SQM,

which sits on the planet’s richest deposit.

Boric’s brand of left-wing politics is much more investor friendly

than that of Salvador Allende, whose 1971 nationalization of US-owned

mines led to the creation of state copper giant Codelco. But there are

signs that the lithium business is about to get increasingly complicated

in Chile, with authorities recently rescinding new contracts amid calls

for the state to get a bigger share of the mineral windfall.

The shifting landscape for the lithium king has its roots in a wave

of street protests in 2019, which led to a rewrite of a constitution

born in the Pinochet era that enshrines private property, including

minerals and water. Writers of a new charter want to tip the balance

back toward community rights, environmental protection and state-run

social services, with a greater say for indigenous groups in where and

how natural resources including lithium are extracted.

Ultimately, the moves could force SQM to adopt extraction techniques

that push up costs or limit production, potentially marking an end to

booming profits. Ponce — Chile’s second-richest person — is the only

disclosed name from the shareholder group, whose entire stake is worth

more than $6 billion. Filings show his portion is equivalent to about

16% of SQM. The shares fell 3.2% in Santiago trading Thursday.

The movement is increasing scrutiny of SQM’s business model, which is

based on pumping up vast amounts of brine from beneath a salt flat in

northern Chile’s Atacama Desert and storing it in giant evaporation

ponds for a year or more — a footprint that can be seen from

space. The resulting concentrate is turned into lithium carbonate and

hydroxide at nearby plants and sent off to Chinese and Korean battery

makers.

As simple as it is profitable, the process uses far less fresh water,

chemicals and energy than hard-rock mining. But the solar evaporation

technique means billions of liters of brine are extracted and then

vaporized in one of the most arid places on Earth, which some say is a

threat to wildlife such as pink flamingos that inhabit its Mars-like

landscape.

Radical proposals such as nationalizing the entire industry have

fallen short in the constitutional process. But if the new charter opens

the way for the mineral-rich brine under the Atacama to be considered a

type of water — an idea the company disputes — that type of mass

extraction may come under threat.

There are already calls from some communities and politicians to move

to a more selective or direct process of mining that would mean far

less evaporation — and probably less output and profit. Both SQM and

Albemarle Corp., the only two lithium producers in Chile, are

investigating such techniques, which are relatively untested

commercially.

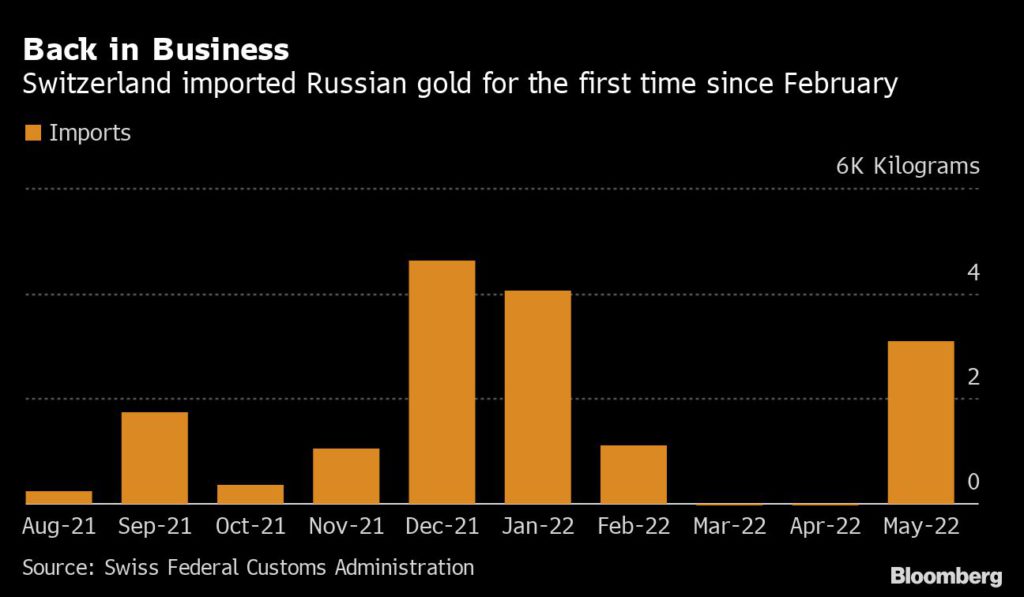

Across the developing world, the growth in EVs has created a new

demand for minerals from Atacama lithium to nickel in Russia’s Siberia

to cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Powering the world with

less fossil fuels presents a new set of social and environmental

challenges. In the short term, it’s made mineral moguls like Ponce

fabulously wealthy.

But the energy transition is leaving behind the communities where the

metals are extracted, says 70-year-old Sara Plaza, an indigenous

resident of Peine, a village near the Atacama operations.

“Mining dried out the salt flats,” she said from her modest home,

with a view to the chalky expanse and mountaintops that surround her

town. “Julio Ponce has done whatever he wanted.”

Ponce’s shareholder group didn’t respond to requests for comment made through SQM.

SQM says it is reducing its brine pumping rates even as it ramps up

production, through efficiencies and by focusing on lithium and less on

minerals used in fertilizers. The company is also spending a lot more

time and money trying to win indigenous groups’ favor, and points out

that its contribution to state coffers of about 60% of earnings is among

the biggest in the industry.

The company has a new marketing campaign that highlights its

contributions, and even plans to put up a sign at its Santiago

headquarters for the first time to boost local visibility. All this

comes as it prepares for talks to renew its mining lease with the

government that expires in 2030.

“We want to tell people what we do,” said Carlos Diaz, SQM’s head of

lithium. Namely, production of a critical mineral that “helps to

decarbonize the world.”

As for Ponce, his journey to lithium king took many twists and turns.

Ponce in 1969 married Veronica Pinochet Hiriart, whom he met because

their families had neighboring beach houses. Four years later, Pinochet

led the bombardment of Chile’s presidential palace in the coup that

brought him to power.

Ponce was working at a sawmill deep in the jungle of the Darien Gap

at the time and heard about the attack from a television in Panama.

Under Pinochet’s rule, his fortunes quickly began to change.

During the dictatorship, the former forestry student was named

president of a state cellulose company, and helped guide its

privatization. He rose to lead other companies controlled by the

government and, eventually, the development agency in charge of

converting state-run enterprises into private businesses, Corfo. The

agency had also commissioned early research on critical minerals in the

Atacama, including lithium.

Ponce stepped away from those roles in 1983 to fight allegations of

illegal enrichment in the acquisition of ranch lands, of which he was

acquitted. When Soquimich, as SQM is also known, sold shares in 1986, he

was back in the privatizations, but this time on the buy side. He and

his family members bought shares, and when Ponce became chairman in

1987, the board was still stacked with military officials. Years later,

Chile’s comptroller found that parts of Soquimich were privatized for as

little as a third of market value.

Maria Monckeberg, a Chilean author who is an expert on the fortunes

derived from Pinochet-era privatizations, said the reforms urged by

economic advisers who studied at the University of Chicago — known as

the Chicago boys — opened the way for Ponce’s wealth boom.

“Thanks to the roles he had in Corfo, he detected the importance of

Soquimich,” Monckeberg said of Ponce. “And he began designing the plan

to own it.”

Chile was only beginning to discover lithium’s potential in the

Pinochet era. A copper miner called Anaconda documented deposits when it

went on a search for water resources in the Atacama desert in the

1960s, according to Monckeberg’s book. In 1969, a research institute

tied to the development agency noted the location of the deposits could

make for relatively cheap extraction.

The lightest metal on the periodic table, lithium was discovered in

1817 by Swedish chemist Johan August Arfwedson, and was initially used

in tiny amounts to treat depression and bipolar disorder. It later

became the focus of military powers interested in the hydrogen bomb, and

eventually researchers found a variety of uses: waterproofing,

gunpowder, heat-resistant glass, air-conditioning and electric car

batteries.

“With bland consistency, white color and surprising properties,

lithium opens the doors to applications of great complexity and

sophistication,” said a 1986 book edited by Gustavo Lagos, a scientist

at Universidad de Chile. Lithium had “an almost magical meaning,

containing in it the hopes that neither copper nor even salt reached in

the life of the nation.”

Ponce became chairman of SQM in 1987 and continued building up his

stake. Six years later, after Chile had returned to democracy, it

obtained a lease for exclusive mineral exploitation rights on 81,920

hectares (202,428 acres) in the Atacama salt flats. The company invested

hundreds of millions at the site, initially with a focus on potash.

As SQM became one of Chile’s most profitable companies, Ponce fended

off a 2006 takeover attempt by PotashCorp. (now Nutrien), North

America’s largest potash producer, by signing a pact with Japanese

trading firm Kowa. In 2018, while no longer chairman but still a large

shareholder, Ponce got a deal to protect the firm’s trade secrets amid

an effort by a larger Chinese competitor, Tianqi Lithium Corp., to take a

stake. Ponce’s brother Eugenio remains an adviser to SQM.

He also endured scandals. He resigned from his decades-long reign as

chairman in 2015 amid a probe over illicit political campaign financing,

which led to a $30 million settlement with

the US Securities and Exchange Commission and a fine for SQM’s then-CEO

(Ponce himself was not charged). Ponce also fought allegations of

market manipulation in courts, and successfully reduced a record $70

million fine — an outcome that critics saw as the sign of a system that unfairly favors elites.

Today, Ponce makes time for visits to his polo club in Santiago, horseback rides at his estate of about 5,000 hectares and even equestrian jumping

during the pandemic. His children sometimes join him on rides — all

four were banned from SQM management in 2018, but not from SQM holding

companies, where his daughters are directors. A Panama-based trust holds

SQM shares for benefit of the family. Ponce keeps family close,

including his brother Gustavo, a yoga guru who has defended Julio on

Chilean TV.

“It’s not easy to be in his position,” Gustavo said of his brother in text reply to Bloomberg.

But a constitutional rewrite represents a challenge that could be harder for Ponce to resolve than his previous court battles.

Cristina Dorador, one of the members of Chile’s constitutional

convention, says the current charter fails to recognize the Atacama salt

flats as ecosystems that are affected when large volumes of brine are

pumped for lithium extraction. A scientist, she has published studies on

the dwindling flamingo presence at lagoons in the vicinity of lithium

mining.

SQM says those studies fail to consider the impact of

tourism on the migratory birds, adding that while lithium production is

up, brine pumping rates are down and food conditions haven’t

changed. Monitoring systems show flamingo populations have remained

stable over time, SQM said, adding that it welcomes scientific efforts

to better understand the relationships between mining and the

environment.

Dorador said the promise of addressing climate change by supplying

the materials needed for a shift to renewable energies has enriched

miners like SQM, but few EV consumers are aware of the new types of

environmental problems that the transition is creating.

“If we are going to do any exploitation then it needs to be done

using the latest in technology and ensure that the consequences are

minimal,” she said. “There has to be a national decision.”

Joe Lowry, founder of advisory Global Lithium LLC, said SQM needs to

address environmental concerns, but at these heights — with a lithium

shortage propping up prices near record highs — it’s not a “major

hurdle,” at least financially. Even a constitutional rewrite is unlikely

to upend forces that are working in Ponce’s favor, he said.

“The new government certainly will not want to stop the massive royalty income,” he said.

(By Blake Schmidt and James Attwood)

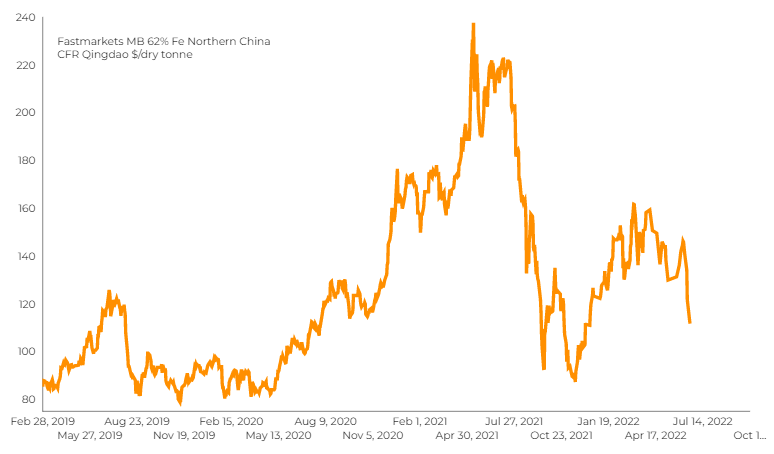

/fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/ce/jnvweowqjvw/China%20iron%20ore%20vs%20price%20June%2022.png_2.jpg)