A floorhand works on an oil rig in the Bakken shale formation outside Watford City, North Dakota.

Getty Images

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/19/why-warren-buffett-is-betting-on-pipelines-evern-as-climate-fears-rise.html

- Major

oil and gas pipeline projects have faced regulatory and political

roadblocks forcing them to halt production or cancel new development.

- The

recent crude oil crash led to a steep reduction in U.S. rig count and

as the shale boom contracted amid a weaker global economy, pipeline

capacity was overbuilt.

- But even as climate change pressures

the fossil fuel industry, natural gas is not going away, say energy

experts, with gas making up 40% of power generation, growing LNG export

markets and more-friendly drilling regions in states like Louisiana and

Texas.

With the coronavirus pandemic slashing demand for

the oil and gas that has been booming in the U.S. shale during the past

decade, energy pipeline development has stalled. The midstream portion

of the energy complex, as it is known, may not recover soon, but it will

recover, according to energy experts, and none other than Warren Buffett — who has been uncharacteristically shy about making investments during the Covid-19

washout — is betting on that. The billionaire investor recently plunked

down near-$10 billion to buy gas pipeline assets and related debt.

After

a decade of capacity buildout in the pipeline infrastructure to match

the U.S. fossil fuel fracking growth, demand is lacking and will stay

down, despite a doubling in the price of crude following sub-$20 lows

reached in March.

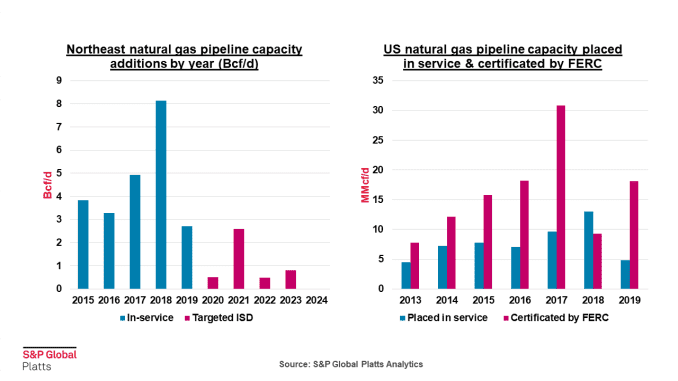

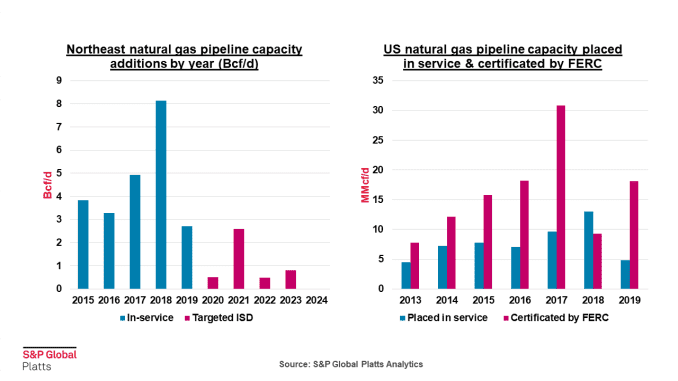

“The

midstream is in a tough spot,” said Luke Jackson, senior analyst,

natural gas, North America, S&P Global Platts. “You have to consider

what drove the infrastructure development: the shale boom. When you

look at oil near $40 and natural gas rising, but still sub-$3, we’re not

in a climate where higher production of oil and gas is supported to

support a larger build out,” Jackson said.

Before Covid-19 hit,

Platts Analytics was forecasting U.S. crude oil production to rise by

one million barrels per day year over year, and rise by another 600,000

barrels in 2021. Now, as rig counts have declined at the steepest rate

since 2009 — 75% of natural gas production comes from the “associated

gas” at oil rig sites, as well — crude production is expected to

register an annual decline within the next few months, and that decline

will persist until at least mid-2021, according to Platts Analytics’

forecast.

Instead of the substantial growth that midstream

companies had been making investment decisions based on — and which led

to a significant number of pipeline projects coming online within the

past two years — major shale basins like the Permian will see lower

utilization of outbound pipelines for the next few years.

Platts

“We’re not expecting U.S. crude to return to

levels we were at in Q1 2020 until 2023,” said Jenna Delaney,

lead analyst, North American oil, S&P Global Platts. “It will be

even a few more years until we get back to where we started from, and

then to satisfy pipeline capacity, we will need even more production

growth.”

But there’s more going on then just a typical

commodities boom-and-bust cycle. With successful environmental

challenges leading to legal and regulatory roadblocks for pipelines, and

a political climate becoming more difficult for fossil fuels, companies

in the utility sectors are rethinking their midstream investments, and

in some cases, reallocating funds towards renewable energy projects.

Earlier this summer, the Energy Transfer-owned Dakota Access Pipeline, which runs from North Dakota to Illinois storage facilities and the Gulf Coast, was forced by a federal judge to

shut down production pending further environmental impact reviews by

the Army Corps of Engineers. The halt in production resulted in a major

win for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, which has been fighting a legal

battle against the pipeline operating and transporting oil for nearly

three years.

“I’m not aware of a pipeline that’s been forced to

shut down mid-production, that obviously concerns people in the

industry,” said Pearce Hammond, managing director and equity research

analyst for midstream and infrastructure at Simmons Energy. “It just

shows how difficult it is to get a pipeline built in the U.S. because of

regulation, environmental concerns, and with environmentalists pushing

against it.”

Dominion Energy and Duke Energy

announced the cancellation of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline due to “legal

uncertainties” surrounding the project. The cost of the project had

increased from nearly $5 billion to $8 billion, amid ongoing legal

battles surrounding permits and environmental issues.

In a separate capitulation, last month Dominion sold its natural gas pipeline assets to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway in $9.7 billion deal that included close to $5 billion in pipeline assets, as well as assumption of debt.

Why Buffett is bullish on gas

According

to Steve Fleishman, managing director and utilities analyst at Wolfe

Research, Buffett’s acquisition will provide a steady stream of revenue

and a quality asset, regardless of the lack of midstream development.

Buffett also has always preferred investments in a market where more

control is reasonable to expect — lack of new pipeline supply could be a

plus as far as his preference for less competition likely to come into

the market. The Dominion gas pipeline and storage assets include

operations in Connecticut, Maryland, Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania,

New York, Maryland and Virginia.

The deal won’t burn a hole in his

pocket, either, with Berkshire sitting on well over $100 billion in

cash and short-term assets, and Buffett always anxious to deploy the

capital into projects that generate a return on investment.

It’s not just the political optics, though that

plays into the shift highlighted by Dominion away from midstream. The

market has been downgrading the value of gas pipeline assets owned by

utilities. Even with one of the biggest utility operations in the U.S.,

Berkshire’s cash hoard can operate like a private equity buyer flush

with cash., Stand-alone utilities, meanwhile, are increasingly focused

on environmentally sensitive portfolios, according to Sophie Karp,

KeyBanc Capital Markets utilities and renewables sector analyst.

“We’ve

seen in the past year, even before Covid, that the premium commanded by

gas assets evaporated,” Karp said. “The market was saying that it

doesn’t want utilities to own gas assets.”

Morningstar analyst

Gregg Warren projects that the Dominion pipeline assets will generate $1

billion in earnings before interest, taxes and depreciation and

amortization, for Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s pipelines unit, which will

see mid-single-digit EBITDA growth. The $9.7 billion deal was estimated

at a price of 9.7 times EBITDA, a price that Dominion management

defended as being above recent, similar transactions.

Assets

like the ones Dominion sold to Berkshire are harder for utilities to

justify given the push among constituents to decarbonize. “The

incremental investor in utilities is more environmentally conscious than

the incremental investor in Berkshire,” Karp said. Referring to

sensitive bases of ratepayers in regions around the country where

utilities are regulated and resistance to fossil fuels are growing. she

added, “A suburb in Boston will not make or break a utility, but it

could be a precursor to ‘a death by a thousand cuts,’ where each

incremental rate case there is more severe opposition to capex that is

not decarbonized.”

“It’s not ‘tomorrow we stop using gas,’ but it

is a plausible scenario where it gets harder and harder for a utility to

put dollars into that infrastructure and derive earnings growth,” Karp

said.

The utilities’ market dynamic partially explains why

Buffett was able to make the deal without paying a hefty premium. “It

wasn’t the top of the market,” the KeyBanc analyst said. “It sold at the

peer group average at a time when the average was down ... but Dominion

was trying to rip the Band-aid off.”

Dominion is moving in another direction, with significant offshore wind opportunities in some of its markets, like Virginia.

“That

may be more attractive than gas, and when can redirect the capex and

get a return on that, and not deal with gas ownership, it looks like a

solid move,” Karp said.

Dominion pointed to the “state-regulated

nature” of its business profile as one of the reasons for the deal, as

well as noting its net zero target by 2050 for both carbon and methane

emissions, and $55 billion planned in next 15 years for emissions

reduction technologies including zero-carbon generation and energy

storage.

Utilities owning midstream gas assets outside their core

business will be slowing down as a business focus, with the premiums

formerly commanded no longer available. Utility stocks did well in

recent years, but “the stocks have not done well on mistream deals,”

Karp said. “The trend will be utilities looking at divesting, not

investing more. ... But natural gas as a fuel is not going away in our

lifetime. The long-term use case is there.”

Concerns about future oil and gas capacity

With

declining access to domestic oil supply as midstream development cease,

some analysts worry about the potential for energy security risks and

the U.S. becoming again reliant on foreign exporters, such as OPEC.

Hammond

at Simmons Energy said the recent regulatory hurdles in the oil and

natural gas markets could ultimately mean, “you’d be relying on

increasing very insecure sources of supply, which is something we’ve

tried to move away from in terms of energy security, turning the clock

back to the 70′s, 80′s.”

“The policy makers are trying to balance

the transition to lower carbon and meet the needs now while still being

energy secure,” he said.

“Certainly, if we see muted or no U.S. production

growth, when demand continues to recover globally, we’re gonna have to

be more reliant on foreign imports that we would have been, certainly

seeing energy security issues,” said Leo Mariani, energy stock analyst

at KeyBanc Capital Markets.

But in the mid-term, what is maybe

more likely is a bifurcation in the U.S. pipeline market, as U.S. oil

and gas production growth comes back, rather than a return to the

OPEC-dictated era.

Platts expects U.S. production growth to start

recovering for U.S. shale by 2023, and does not expect midstream

constraints, especially as Canadian crude continues to flow into the

U.S. and the export market for liquified natural gas continues to grow.

“We

do believe that the U.S. will need more infrastructure development to

support higher movement of gas to markets in the Gulf Coast, in East

Texas and Louisiana,” Platts’ Jackson said.

The situation in markets like the Northeast and its big population centers will be more challenging for building pipeline.

“It

will be much easier to build pipelines in certain areas,” said Eric

Brooks, Northeast US natural gas analyst, S&P Global Platts. “In the

Northeast, it’s a more intense regulatory environment and that does

come back to politics. Atlantic Coast Pipeline was emblematic and it is

no secret it is challenging environment.”

Broader market shift to renewables

What is happening at Dominion is also occurring within the oil and gas industry. BP recently took a step that would have once been considered unthinkable when it reported a loss

of $6.7 billion — the oil and gas giant halved the dividend that has

long been coveted by pension fund investors and committed to a new

strategy of increasing investments in renewable energy and cutting oil and gas generation by 40%.

Equinor,

the Norwegian petroleum company formerly known as Statoil, also is

transitioning its business model to include more renewable energy,

including offshore wind projects as its primary way to accelerate a

transition to low-carbon energy sources. The changes, though, are less

than absolute: Equinor’s near-record breaking offshore wind project will provide renewable energy to oil and gas platforms.

“They can see clearly that something needs to be

done about climate change,” said Andrew Grant, head of oil and gas for

Carbon Tracker, a think tank that focuses on the financial and market

implications of climate change. “An increasing numbers of countries

around the world have set zero targets .... we’re going to need other

alternatives and less fossil fuels, and companies understand that, and

they want to build in some future-proofing ... to build out some of

those energy sources. They’re stuck between that and the fact they have a

very long history of producing oil and gas fields,” Grant said.

A report from

Rystad Energy forecasts the global number of drilled oil wells to be at

55,350, the lowest number of wells since the early 2000s and a 23%

decline in the number of wells drilled in 2019. Even further, North

American drilling is expected to remain 50% lower than last year’s

levels.

“A lot of pressure is coming through from all

stakeholders, consumers, and civil society, but also investors,

especially in the past few years. Investors realize there is a risk and

they want to be reassured. It has become clear that oil and gas

companies have underperformed in the market. Investors realize that the

world is going to decarbonize,” Grant said.

For Dominion, the business model is changing more quickly.

“They

made a decision to exit this midstream pipeline business because they

basically felt that it [renewable energy] would be a better business, it

would basically accelerate the transition of the company to clean

energy, For them, it’s a pretty big strategic bet they made,” Fleishman

said. “They’re making a bet the new model of the company will have

better growth and better financial strength and more focus on clean

energy will get a higher valuation.”

Even as he increases his

pipelines footprint, Buffett’s utility has been making a considerable

shift. It is already one of the biggest wind energy producers in the

U.S. through its MidAmerican Energy utility affiliate based in Iowa,

while its NV Energy in Nevada plans to increase its renewable generation

to a percentage in the high 40s by 2023, mostly using geothermal and

solar power.

Some make the case that the Buffett pipeline buy is about electric vehicles

playing a bigger role in the future. But in a broader sense, Buffett

has parted ways with a strict decarbonization investing philosophy in a

core belief that he outlined to Berkshire shareholders who were concerned about climate change

back in 2014. Buffett said that whether the investment decision was

about Berkshire Hathaway or “virtually all the companies I can think

of,” he didn’t believe that “climate change should be a factor in the

decision-making process.”

—Additional reporting by Eric Rosenbaum