https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pdvsa-trade-partners-exclusive/exclusive-pdvsas-partners-act-as-traders-of-venezuelan-oil-amid-sanctions-documents-idUSKBN1ZC14U

CARACAS/PUNTO FIJO, Venezuela (Reuters) - Venezuela, its oil exports

decimated by U.S. sanctions, is testing a new method of getting its

crude to market: allocating cargoes to joint-venture partners including

Chevron Corp (

CVX.N), which in turn market the oil to customers in Asia and Africa.

This would not violate sanctions as long as sale proceeds are used

for paying off a venture’s debts, according to three sources from joint

ventures. They said this approach could help Venezuela overcome

obstacles to producing and exporting oil.

Venezuela’s oil

exports fell 32% last year as the U.S. government blocked imports by

American companies and transactions made in U.S. dollars. PDVSA was

forced to use intermediaries for crude sales as Washington pressured

Venezuela’s Indian and Chinese customers to halt direct purchases.

The

sanctions were designed to oust Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro

after most Western nations branded his 2018 re-election a sham.

By acting as an intermediary for PDVSA’s oil sales, Russia’s Rosneft (

ROSN.MM)

in 2019 became the largest receiver of Venezuelan crude, using the

sales to amortize billions of dollars in loans granted to Venezuela in

the last decade.

Washington has mostly allowed mechanisms to pay

off debt with oil or to swap Venezuelan crude for imported fuel, but

Venezuela’s opposition is lobbying the U.S. administration to punish

intermediaries.

PDVSA, the U.S. Treasury Department and the State Department did not answer Reuters’ requests for comment.

The

latest tests of the policy come this month. A 1 million-barrel cargo of

Venezuelan upgraded crude consigned to Chevron is scheduled to load at

PDVSA’s Jose port, according to internal documents from the state-run

firm seen by Reuters.

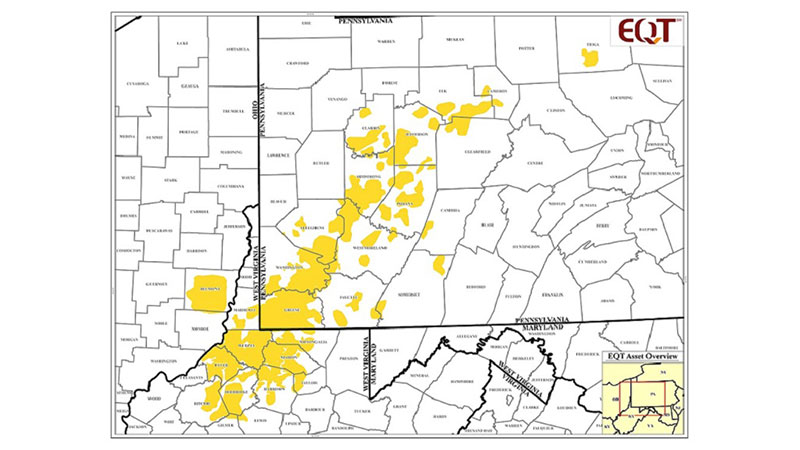

Chevron has a stake in the

Petropiar joint venture with PDVSA to upgrade oil in the OPEC nation’s

Orinoco belt, one of the world’s largest oil reserves. Chevron’s license

to operate in Venezuela despite sanctions expires on Jan. 22 unless the

U.S. Treasury renews it.

“Proceeds from these marketing

activities are paid to our joint venture accounts to cover the cost of

maintenance operations, in full compliance with all applicable laws and

regulations,” said Chevron spokesperson Ray Fohr.

In the past, Chevron itself used to refine Venezuelan crude at its U.S facilities, often bought from PDVSA’s joint ventures.

Another

cargo of 670,000 barrels of Tia Juana and Boscan crudes, chartered by

Venezuelan oil firm Suelopetrol, set sail at the beginning of January,

the documents showed.

Suelopetrol, a minority stakeholder in

joint ventures with PDVSA, said it was recently allocated a Venezuelan

crude cargo under contracts signed prior to U.S. sanctions with PDVSA

and joint venture Petrocabimas to support investment and development of

oilfields.

“Those contracts include the designation of

Suelopetrol as offtaker of crude produced for compensating accounts

receivable, due since 2015, for capital contributions, technical

assistance, provision of services and accumulated dividends,” it said in

response to questions from Reuters.

By Venezuelan law, state-run

PDVSA is required to market all Venezuela’s crude exports, except for

upgraded oil, whose output was suspended in 2019 due to accumulation of

stocks. Only Petropiar, one of four upgrading projects in the Orinoco,

has recently resumed operations.

To avoid violating Venezuelan

law, the joint ventures that are not allowed to market their output for

exports first sell the oil to PDVSA, which then allocates the cargoes to

its joint venture partners, according to two of sources and documents.

The

private partners take possession of the cargoes at Venezuelan ports and

transport them in chartered vessels to refineries around the world,

according to the documents and tanker tracking data from Refinitiv

Eikon.

Proceeds from these sales to ultimate buyers are being

transferred to the joint venture’s trustees to fund operational expenses

as well as paying debt and dividends owed to partners.

“It is a

matter of life or death for joint ventures to achieve this so operations

can restart,” said a top executive from one of the joint ventures that

accepted the mechanism.

According to the PDVSA documents and

sources, Chevron took two cargoes of Venezuelan Boscan and Merey crudes

in the last quarter of 2019, before lifting a cargo of Hamaca crude in

January. Suelopetrol’s cargo, on tanker Ace, set sail on Jan. 5.

ACCUMULATED DEBT

Several

of PDVSA’s more than 40 oil producing joint ventures owe hundreds of

millions of dollars to minority partners as PDVSA demanded from 2013 to

2017 they extend funding to the projects.

Minority stakeholders

put the money through credit lines and loans backed by supply contracts

so sale proceeds would go to trustees for paying the projects’ costs

while amortizing the loans.

But U.S. sanctions deprived PDVSA and

some joint ventures of the supply contracts used to guarantee the

loans, leaving the projects without sources of cash and freezing the

credit lines.

The new mechanism is intended to unfreeze cash

flow to continue production, the sources said. It could also make it

easier to trade Venezuelan oil by using joint-venture partners as buyers

or traders while sanctions are in place.

Very high

freight tariffs for transporting Venezuelan oil, the difficulty in

finding willing buyers, and problems at oilfields and shipping terminals

remain obstacles to implementing the mechanism, the sources added.

Lawyers

consulted by some PDVSA partners interested in lifting Venezuelan crude

told them the sales are allowed under sanctions as long as proceeds

paying off debts remain out of Maduro’s reach, which is the main

intention of the measures, one of the sources said.

Reporting

by Marianna Parraga in Mexico City, Mircely Guanipa in Punto Fijo,

Venezuela, and Deisy Buitrago and Luc Cohen in Caracas. Additional

reporting by Timothy Gardner in Washington; Editing by Daniel Flynn,

Gary McWilliams and David Gregorio

:brightness(10):contrast(5):no_upscale():format(webp)/GettyImages-186451171-58c395263df78c353cf8aa50.jpg)