https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-26/giant-oil-tankers-from-u-s-seen-cutting-time-money-and-traders

-

LOOP deepwater port to simplify export logistics: Braemar ACM

-

Medium-sour crude exports in focus with time and cost savings

Big oil tankers sailing from the U.S. are set to bring along some

benefits for refiners in Asia while allowing them to sidestep traders

serving the world’s top crude-buying region.

The

new option to load oil into very large crude carriers at the U.S. Gulf

Coast terminal operated by the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, or LOOP,

will reduce costs and waiting time for Asian buyers of American

supplies, according to shipbroking firm Braemar ACM.

It also reduces the need to rely on traders to manage complicated

tanker logistics that sometimes involve multiple smaller vessels

transferring crude into a bigger boat.

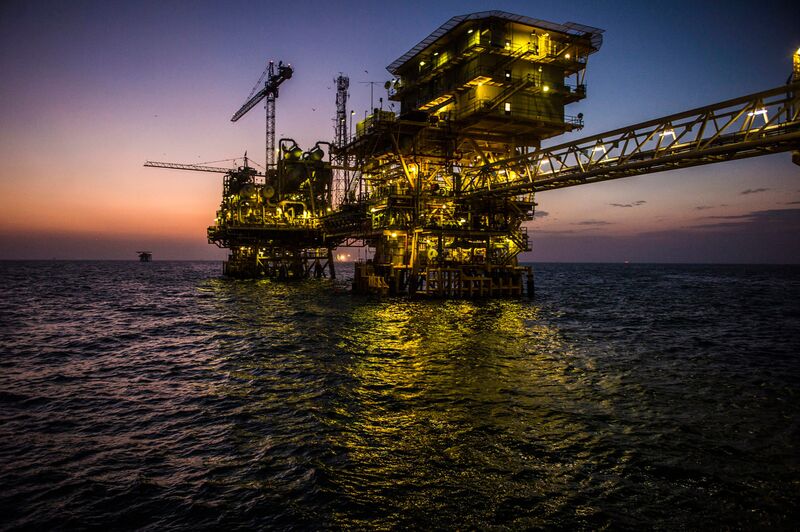

The first fully laden supertanker sailed from

America earlier this month, leaving for China from LOOP’s deep-water

facility -- the only one in the U.S. capable of filling some of the

industry’s biggest tankers. In the wake of an end to a four decade-ban

on exports and as OPEC curbed output to clear a glut, a stream of shipments from the Gulf Coast headed east as major buyers such as India and South Korea looked farther for supplies.

The ability to export via the big ships may prove a blow to

traders and their role as middlemen at a time of increasing efficiency

and improved market transparency.

Until now, Asian refiners have mostly purchased U.S. oil that’s sold to

them on a delivered basis by traders, who would source the cargoes,

load them onto smaller vessels and arrange for out-at-sea transfers to

supertankers that can’t enter the shallow berths of most American

terminals.

While

it offers cost and time advantages, “the bigger win for Asian buyers,

however, may be the ability for buyers to cut out the trader’s margin by

using LOOP,” Anoop Singh, an analyst at Braemar ACM, wrote in a

tanker-market report. “This is because most buyers of U.S. crude in Asia

take delivered barrels from traders, which have traditionally been

better at managing” the shipping logistics, he said.

To be sure,

traders are unlikely to lose all their business. Braemar ACM expects

LOOP shipments to average only 1 to 2 VLCCs a month, still leaving

plenty of other opportunities for crude to be exported from smaller

terminals.

Cost savings

Loading about two million

barrels of oil into a VLCC at LOOP could cut about $300,000 in direct

costs -- or 20 cents per barrel -- compared with the current process of

chartering several Aframax vessels to load barrels from inland berths

and ship-to-ship transfers to larger tankers, according to Braemar ACM.

Additionally, loading at the terminal also reduces the timeline to one

day from the four days that’s currently needed.

To sweeten the deal, LOOP is also willing to offer storage space in its tanks

at discounted rates to enable exporters to collate enough volumes to

fill a full VLCC. It has storage capacity of 71 million barrels, nearly

as large as the 78 million barrels at U.S. oil hub in Cushing, Oklahoma,

Singh said in the report.

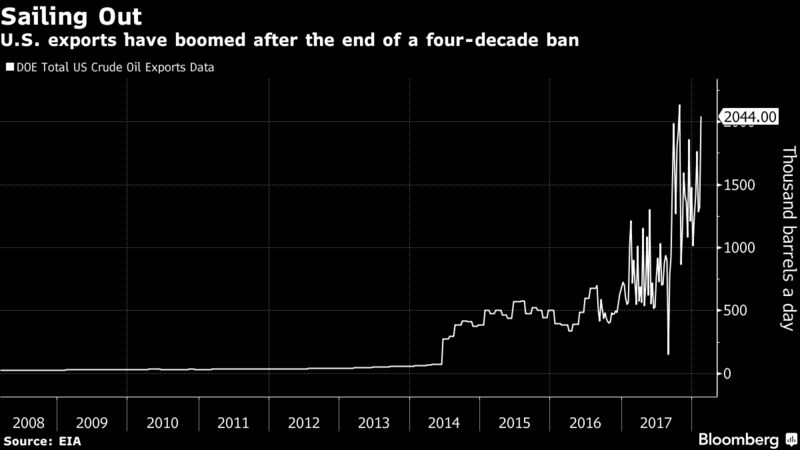

Based on the shipbroker’s estimates, U.S. exports have

averaged 1.4 million barrels a day this year, rising from 2017 when 1

million barrels a day were shipped from its ports. About nine VLCCs a

month departed during the fourth quarter of last year, with more crude

bound for the east of Suez market. Those large ships were loaded using

supply initially ferried by smaller tankers.

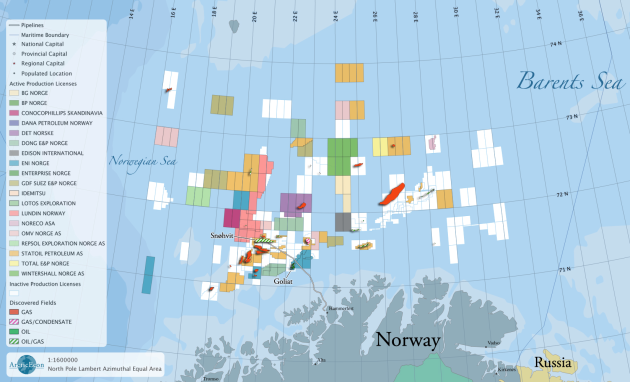

Oil Quality

The supplies exported via LOOP may be focused on crude of so-called medium-sour quality, Singh wrote in the Feb. 23 note. That’s due to direct pipelines linking the most abundant Gulf of Mexico fields such as Mars, Poseidon

and Thunderhorse to LOOP’s storage terminal, bringing in more than

500,000 barrels a day of production. These are different in

characteristics to light-sweet oil from shale fields, supplies from

which have pushed American output to a record.

“LOOP’s pipeline

capacity has limited ability to bring in light-sweet crudes,” Singh

said. “Production of these crudes from Permian, Eagle Ford and Bakken

regions is growing fast. But these grades are primarily being exported

from ports in Texas because of better pipeline connectivity.”

West

Texas Intermediate crude, the U.S. benchmark, traded at $63.54 a barrel

at 5:22 a.m. in New York. Prices are up about 5 percent this year.