We may never fully know what lies behind Crown Prince Mohammed

bin Salman's decision to arrest more than 200 Saudi citizens, including

11 princes and four government ministers, on corruption charges, just

as tensions with Iran are escalating.

What we do know is that his

move simultaneously boosted the oil price and undermined the

attractiveness of Aramco to potential foreign investors. But it would be

a mistake to conclude that this political decision also heralds a shift

in Saudi oil policy, or permanently damages the prospects of the state

oil company's IPO.

Crude prices always rise in response to unrest

in the Middle East, even when the countries involved produce little or

no oil. That it has done so now, in the wake of the arrests in the

region's biggest producer and the threats against Lebanon and Iran in

response to a missile launched from Yemen, should come as no surprise.

The

jump, which took oil prices to their highest level in more than two

years immediately after the arrests, might be expected to boost support

for a pause before OPEC and its friends decide whether to extend their

current deal on production cuts until the end of 2018. There are some,

including Russian President Vladimir Putin, who have said that it is too

early to decide what should be done beyond the deal's current expiry in

March.

But dissenting voices are likely to fade into the

background when the groups meet in Vienna on Nov. 30. The output cuts do

not target a specific oil price -- as Saudi oil minister Khalid

Al-Falih said in June, the aim is to reduce excess inventories. That

problem has not yet been resolved.

MbS,

as the crown prince is widely known, is already setting the kingdom's

oil policy. He turned on its head Saudi Arabia's earlier stance of

boosting oil supply in an attempt to drive out higher-cost producers,

and he has placed his country at the forefront of output cuts aimed at

draining excess inventories, cutting production by more than required

under the agreement. He has already expressed support for extending the

production deal. Only by returning global oil inventories to more normal

levels can Saudi Arabia, and OPEC, hope to return to a world where

their actions influence the market.

The Saudi anti-corruption

purge should change nothing for the kingdom's oil policy. MbS is surely

mindful that an extension of the current output deal has already been

priced into the market, and failure to deliver it at the end of the

month would kill the recent rally in prices, despite the elevated

tensions in the Middle East.

Assessing the impact of the

detentions on the Saudi Aramco IPO is less straightforward. Ninety-five

percent of the shares will remain the property of what is now clearly an

unpredictable government. If the arrests turn out to be no more than a

purge of opponents to the crown prince's accession to the throne,

potential investors will run for cover.

But perhaps the anti-corruption purge is

the first step towards creating a more open and dynamic business

environment in Saudi Arabia. If it truly marks the beginning of the end

of the of the rentier state that has crippled the country's development

then it could even improve the prospects for inward investment, and

boost the attractiveness of the shares.

Foreign investors'

appetite for a piece of a partially-privatized Saudi Aramco will not

depend on whether the price of oil at the time of listing is $50, $60,

or $70 a barrel. A decision to invest in the company will depend much

more on the dividend and taxation policies of the major shareholder --

the Saudi government -- and the investor's view of the long-term future

for oil.

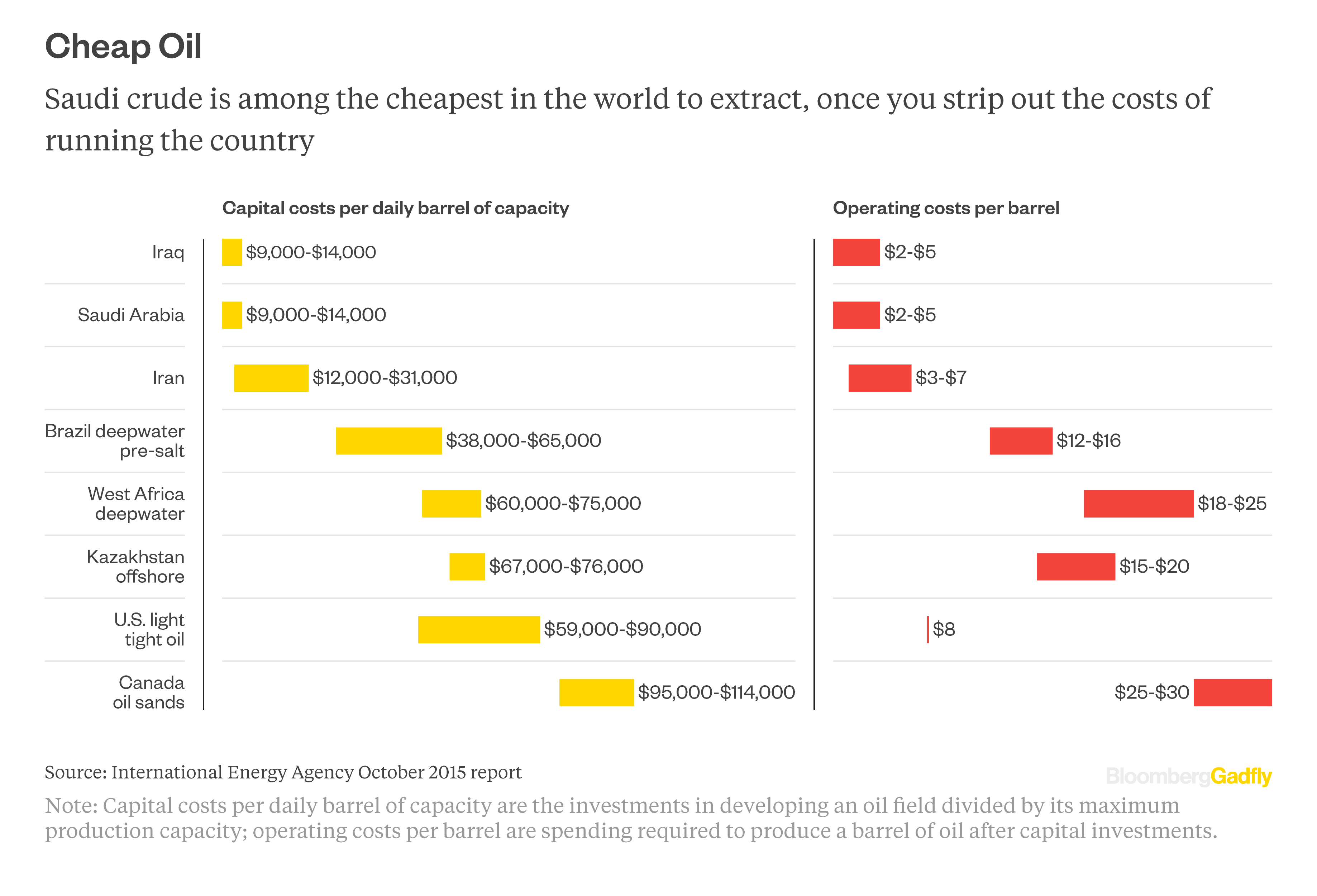

Indeed, it could be argued that over the longer term Aramco would benefit from a lower oil

price, which simultaneously boosts demand for crude and makes

alternative energy sources less attractive while undermining other,

higher-cost oil supplies. That ought to give the best outlook for

production as Aramco still extracts some of the lowest cost oil on the

planet. If Saudi Arabia's "Vision 2030" plan to wean the kingdom off its

dependence on oil revenues is even partly realized, Aramco will be

relieved of much of its burden of supporting government expenditure.

That should serve to burnish the appeal of the shares.

To realize

his dream of privatizing Aramco -- and the planned 5 percent offering

may be only the beginning -- the young crown prince will need to show

hoped-for investors that his recent purge of the kingdom's elite really

is a first step on the road to a brave new Saudi Arabia.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

No comments:

Post a Comment