A row is brewing about whether the London Stock Exchange should bend its rules by allowing Saudi Arabia's state oil company to join its benchmark indexes as it tries to win the initial public offering for the U.K.

Enlightened self-interest suggests the LSE should sacrifice the listing to safeguard the credibility of its index business.

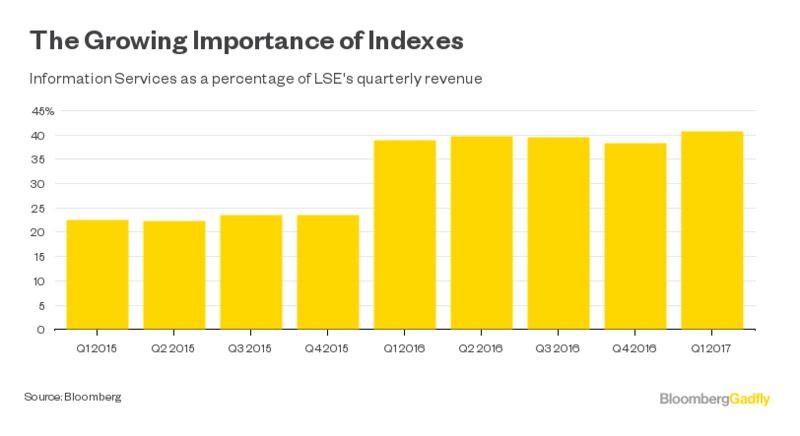

The explosive growth of passive investing, with its index-matching strategies, is making the indexing business increasingly important to the world's exchanges.

LSE's revenue from capital markets (the business that earns fees from companies going public and from secondary market equity trading) declined for a seventh consecutive year to less than 24 percent of total income last year, down from almost 50 percent at the start of the decade. By contrast, the company's information services unit (which includes the index-licensing business) has expanded to account for more than 40 percent of revenue in the first quarter of this year.

The LSE has been at the forefront of a flurry of consolidation in the world of indexing in recent years. It paid $2.7 billion for Frank Russell Co. in 2014, subsequently changing the name of its index business to FTSE Russell. Last week, it paid $685 million to buy Citigroup Inc.'s fixed-income analytics and index unit, increasing the value of assets using FTSE Russell indexes to more than $15 trillion.

It's not alone, though. Intercontinental Exchange Inc., owner of the New York Stock Exchange, and Bloomberg LP (Gadfly's parent company) have also acquired bond-index businesses in recent months.

As competition to provide the indexes of choice for exchange-traded funds and their fellow index-following brethren increases, the last thing the LSE can afford is to annoy investors by effectively forcing them to buy shares in companies it adds to its indexes in breach of its own regulations.

As things stand, Saudi Aramco shouldn't make it into the FTSE indexes. The planned IPO would deliver at most 5 percent of its shares into investors' hands, far below the 25 percent free-float minimum the LSE demands for inclusion in its benchmarks.

The concern is that with 95 percent of Saudi Aramco controlled by the state, investors will have almost no say in how the company manages its affairs. (There's a similar objection to including Snap Inc., the photo app maker, in U.S. indexes because its $3.4 billion IPO in March was compromised solely of non-voting stock.)

The U.K. Investment Association, a trade group representing about 200 funds, has specifically opposed giving the Saudi firm special treatment. "Twenty-five percent should be the minimum free-float level for any premium listed company in the U.K.," it said in a May 5 statement. "Saudi Aramco is no exception."

Growing the indexing business is a key component of the LSE's strategy. ETF providers, though, are beginning to balk at the charges levied by providers and may band together to create their own index company; the Financial Times last month quoted Lynn Blake, chief investment officer for State Street Global Advisors’ passive equities business, as suggesting "something like self-indexing or other alternatives to keep costs lower while providing the same services to our clients."

London is competing with New York, Hong Kong and Tokyo, among others, for the Saudi behemoth's foreign listing. In April, LSE Chief Executive Officer Xavier Rolet accompanied U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May on a visit to Saudi Arabia to pitch for the listing.

But if the price of winning that beauty parade is to tick off investors who'd rather not add Saudi Aramco to their passive portfolios, LSE would be better off losing to the competition.

No comments:

Post a Comment