President Muhammadu Buhari

- Country needs $15 billion to boost economy, reserves: Dangote

- Sale amid low crude prices may affect assets’ value: analyst

Nigeria’s possible sale of some of its oil and gas assets to raise

money and boost the contracting economy in Africa’s most populous

country could reduce the government’s influence over its biggest

industry.

President Muhammadu Buhari’s economic advisers are

working on a plan “to generate immediate large injection of funds into

the economy through asset sales, advance payment for license rounds,

infrastructure concessioning,” to help deal with the slump in oil

revenue, Budget Minister Udoma Udo Udoma said in a Sept. 24 statement.

The ministry of Petroleum Resources is examining what oil assets could

be sold, Udoma’s spokesman, James Akpandem, said last week.

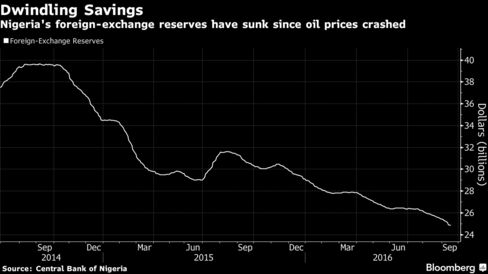

Battered by low oil prices and a dearth of foreign investment, Nigeria’s economy will probably shrink

in 2016 for the first time in 25 years, according to the International

Monetary Fund, which forecasts a 1.8 percent contraction. A 15-month

currency peg, fuel and power shortages and a slump in crude production,

have cut output. The country’s foreign-exchange reserves have fallen by

more than a third since the end of September 2014 to $24.8 billion.

Selling

upstream assets “will most likely change the structure of the Nigerian

oil industry,” Chijioke Nwaozuzu, a professor at the Institute of

Petroleum Economics at the University of Port Harcourt, the country’s

oil hub, said by phone. A transfer of petroleum reserves to private

investors would diminish government influence in the sector, likely

resulting in improved efficiency and capacity utilization and “it could

also mean mortgaging future crude-oil exports,” he said.

Nigeria

has an average 55 percent stake in joint ventures run by Royal Dutch

Shell Plc, Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp., Total SA and Eni SpA. These

account for about 90 percent of Nigeria’s oil production, which

generates roughly two thirds of government revenue. The state also owns

49 percent of Nigeria LNG Ltd, a multibillion-dollar company which

operates Africa’s biggest liquefied natural gas plant.

The sale of

such stakes, augmented by offshore borrowing, would help the country

raise the $15 billion that is needed to revive the economy, Africa’s

richest man, Aliko Dangote, said in an interview with Bloomberg TV on Sept. 22.

Repurchase Clause

If

the authorities decide to proceed with the sale of energy assets “it

will ideally be to the existing partners who wish to increase their

share,” Udoma’s spokesman, Akpandem, said. Any such deal would include a

repurchase clause, he said.

“We’re

looking at this very feverishly because the other alternative is to go

mass borrowing,” State Minister for Petroleum Resources Emmanuel

Kachikwu said in an interview last month. “But there’s a limit to your

borrowing cap and we’re fairly close to that tipping point where you

really can’t borrow anymore otherwise you can’t sustain the borrowing.

The other thing to look at is your assets and rights that can be turned

into cash.”

Buhari approved a 6.1 trillion naira ($19.4 billion) budget for this year and said he expected the government to raise about $5 billion from the Eurobond market and multilateral lenders.

Higher

borrowing costs and the loss of almost half of the revenue projected

for this year could push Nigeria’s debt service-to-revenue ratio above

the projected 35 percent, according to documents from the budget and

national planning ministry.

Dangote

has recommended the state parts with some of its shares in NLNG,

jointly owned with Shell, Total and Eni. Senate President Bukola Saraki

has advocated for the sale of oil and gas interests and the

privatization of airports and refineries, while former central bank

governor Muhammadu Sanusi II said parting with assets could be done

without hurting the government’s strategic interests and would give

incentives to private investors.

Oil workers warned on Sept. 25 that they would go on strike if national assets were sold.

Unfavorable Timing

“Given

the economic situation and the challenges, the rationale is there,”

Rolake Akinkugbe, head of energy and natural resources at Lagos-based

FBN Quest, said by phone. Nigeria is likely to do away with those oil

fields where it has struggled to meet its share of capital

contributions, leaving it with arrears of about $6 billion, she said.

The

timing though, with oil prices at about half their 2014 levels and

insecurity in the Niger River delta where militants are sabotaging oil

and gas infrastructure, may not be right, according to Ayodeji Dawodu, a

research analyst at Lagos-based Investment One.

“If it is because

the economy is in an emergency, and you’re able to put in a buy-back

clause, then it may be justified,” he said by phone. “There has to be a

trade off and they should know what they’re trading off.”

No comments:

Post a Comment